Dear Motley Crew,

Here we were once again at Autherley Junction, the end point of the Shropshire Union canal, with just one lock now between us and our appointment with the Wolverhampton 21.

A right-hand turn here followed shortly after by a left-hand turn and there it was – the bottom of the flight.

Lock number 21 - it’s all up-hill from here

As I wandered nonchalantly up to the lock gates, windless in hand, it occurred to me just how far we’d come, in terms of experience, over the last two years. At the outset, when faced with the Hatton locks – my first, long flight of locks – I had been filled with anxiety and a degree of apprehension. Would I be able to manage the heavy gates and paddles on my own? Would I have the stamina to keep turning and lifting and pulling and pushing for over four hours? And yet here I was, some 24 months later, casually approaching a flight of 21 whilst contemplating the choices for that evening’s dinner.

Four hours later, and after a climb of 132 feet, we found the lock that we’d been looking for – the last one!

Our arrival into Wolverhampton catapulted us once more into an urban environment where graffiti was the order of the day,

and abandoned warehouses and factories, sprouting opportunistic growths of buddleia, lined the canal.

Fortunately, not all of the city’s industrial architecture has met the same fate, and this rather majestic Chubb Lock Works factory, has been afforded a new lease of life as an office block.

Graffiti and derelict buildings were not the only indication that we were now travelling through an urban environment. The state of the canal also left us in no doubt as to our whereabouts. Formally clear water was now green-tinged and murky, and floating weeds, the blight of narrowboaters' lives, were growing in thick swathes along the edges of the canal, and impinging into the channel.

Inevitably, the Captain was forced to make multiple excursions down into the weed hatch, from whence he emerged with coils of tangled weed, lengths of fishing line and string and, in a first for us, an Indian shawl.

We passed by Horsley Fields Junction, the entrance to, or the exit from, the Wyrley and Essington canal. It was from here that we had emerged somewhat bruised and battered last year following our ill-fated visit to Walsall.

No turning off today however, for today we would be continuing straight ahead towards Birmingham and hereto unexplored territory. “How exciting”, She was heard to murmur, “something new.”

When planning our route, “the something new” had seemed relatively straightforward; simply head along the canal into Birmingham. A cursory consultation with the Guide, however, revealed that there were some serious decisions to be made, and the more we consulted the Guide, the more confusing and complicated it became. Should we take the New Line into Birmingham or the Old Line? Indeed, what was the difference? Was one better than the other? And what, in heaven’s name, was the deal with all of those loops and branches?

In the end, after considering the options and deciphering the map, we plumped for the no-nonsense New Line. Built by Telford in1838 to replace Brindley's meandering Old Line, the New Line runs as straight as a die for three miles, and is interrupted only by these former toll-house islands. That be the one for us then.

The island design meant that tolls could be collected from boats travelling in each direction

Today's over-grown edges call for a steady hand upon the tiller when passing the islands

A steady hand was also needed to navigate through Coseley Tunnel, though at a mere 360 yards, we were at the end before we knew it.

Perhaps that was a good thing as the tunnel is reputedly haunted by the White Lady, one Hannah Johnson-Cox, who, after having been abandoned by her sottish husband, drowned her two youngest children in the waters of the tunnel. It is said that she roams the area still, seeking out her little ones. Mercifully, on the day that we chugged through, she was nowhere to be seen.

What could be seen in the distance however, were the massive pylons of the M5, sitting solidly and squarely amidships in the canal, requiring narrowboaters to again, track a steady course.

This, however, turned out to be a delightful coming together of both present and past means of transport. The two-arched bridge under which we passed, is actually an aqueduct that carries Brindley's Old Line canal over Telford's New Line canal. To the left is the railway, which, in effect, replaced the working boats of the canal, and soaring far above it all, is the M5. How remarkable!

Also remarkable was the proud, old factory which we were now passing; the former site of the Chance Glassworks.

This was no ordinary glassworks, for this factory had an impressive list of projects to its credit; the glazing for the Crystal Palace in London and the Houses of Parliament; the opal glass on the four faces of the Westminster Clock; and the ornamental windows for the White House. But for me, the most fascinating fact was that they also manufactured crown and flint glass for lighthouses, and supplied specialist lenses to over 2,000 lighthouses across the world. I had desperately wanted them to have manufactured the glass for my favourite lighthouse - The Bell Rock lighthouse - but sadly, it was not so.

We almost had need of a lighthouse on our run into Birmingham - early intermittent showers had become persistent showers, and then morphed into heavy, unrelenting rain and fog. We limped into the centre, moored up, and hoped for fine weather on the morrow.

And fine weather we were given. Although quite cold, the rain had stopped and Birmingham showed itself at its best.

One of the most amazing things about narrow-boating is the opportunity it affords to be able to cruise through - and moor up in - the centre of a city. Birmingham is a spectacular example of this and although it has something of a reputation for bovver boys and attacks on boats, we found it to be both safe and welcoming.

The run out of Birmingham by canal is rather disquieting. One moment you're in the CBD surrounded by office blocks and shops, and the next, after taking a turn to starboard, you're suddenly in the country.

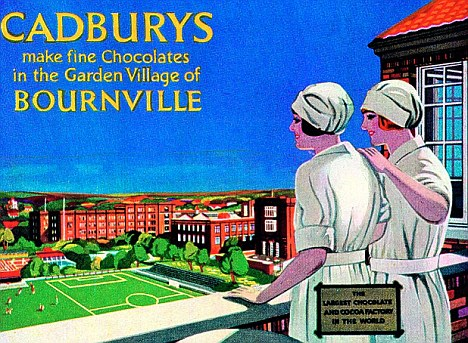

It was this search for a rural environment and the need for space that drove the Cadbury brothers in 1878, to move their chocolate-making factory out of Birmingham city to a large acreage near to the Bourn River, and on the banks of the canal. Devout Quakers, and pioneers in industrial relations and employee welfare, they asserted that an industrial area need not be squalid and depressing. "No man," they said "ought to be condemned to live in a place where a rose cannot grow." To this end, they set about creating Bournville, the "factory in a garden".

Your nose alerts you to the factory's presence long before you arrive

The Worcester and Birmingham Canal was proving to be full of delightful surprises and touches of whimsey. Thus far we had encountered lighthouse glass makers and creators of fine chocolate, but at Kings Norton Junction, we came upon the church of St Nicholas, and the parish of Kings Norton, one-time abode of a young curate by the name of Rev W. Awdry, creator of Thomas the Tank Engine.

Lighthouses, chocolate and trains - what more could you ask for?

Well, as it happens, a whole lot more, for we soon found ourselves at a crossroads. Should we continue along the Stratford Canal towards Stratford-upon-Avon, or should we take the arm that would take us back to the the Grand Union? Shakespeare beckoned, but, in the end, the decision was made for us, as we had a schedule to meet, and we were fast running out of time. Left it was then, onto the familiar territory of the Grand Union.

The miles began to slip by now. Through Shrewley Tunnel,

and then, in the most amazing weather, down the 23 double locks of the Hatton flight, that dropped us one hundred and fifty feet into the town of Warwick,

where we paused for a day or two to explore the market town,

and its imposing castle.

We were now back on familiar ground - or water - with the miles decreasing between us and Blisworth. Ahead of us lay 36 locks, but our pace had slowed somewhat, for we were fully aware that this was the last leg of our adventure, and we felt the need to take our time and savour this final run.

It was with heavy hearts that we turned off the Grand Union Canal into Blisworth Marina for the last time, for now would begin the task of packing suitcases, and readying Matanuska for sale. "Ah", She said "home for the winter months. How delightful." If only She knew.

The Captain, The Commodore and Mrs Chippy

Opmerkingen